notes from an unruly body: Discovering Brad Lomax

Civil Rights leader, Black Panther, and radical disabled activist

In this month’s column we’re leaping forward, cat-like — some might even say, Panther-like — through time, to talk about a man whose activism is still felt across the United States today. These days, most of us have heard of intersectionality, but Brad Lomax (1950 – 1984) was a uniting thread in both the Civil Rights and the disability communities of the 1960s and 70s.

Born Bradford Lomax in September of 1950, he was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis when he was still just a teenager studying at Howard University in Washington. With his illness progressing quickly, it wasn’t long before Brad became a wheelchair user. Already a member of the Black Panther Party, the sudden onset of his MS opened his eyes to other forms of discrimination, and he would go on to make history as a key link between two communities who were determined to rise up together.

Independence and resistance

A founding member of the Black Panther Party’s Washington chapter in 1969, Brad was committed to a revolutionary politics that centred Black empowerment, racial equality, and the eradication of poverty and state brutality. Although he’d already been diagnosed when he founded the chapter, he still worked tirelessly to organise the first African Liberation Day demo in 1972, bringing together tens of thousands of protestors on the National Mall in solidarity with African nations still fighting for independence.

It was only a year later that he moved to Oakland, California, where the burgeoning justice movements for gay rights, Native American rights, and disability rights were also beginning to make themselves known. At the time, there were few legal imperatives to ensure public access for disabled people, with many hidden away in institutions, barred from education and work, and with few services to help them to access appropriate housing or support. For Black disabled people in particular, there was even less support, and little acknowledgement of the additional barriers that were placed in their way.

The Centre for Independent Living had already been established by a group of disabled activists in the city, campaigning for curb cuts for wheelchairs and other access measures in San Francisco and Berkeley. Recognising the power of intersectional solidarity, Brad worked with their director, Ed Roberts, and the centre combined forces with the Black Panthers to offer assistance to Black disabled people in East Oakland. This early collaboration would prove crucial in the fight for disability rights nationwide.

Black Power and 504

In the same year, the rehabilitation act was first proposed. Buried in its provisions was Section 504, which would guarantee for the first time that any building or organisation in receipt of federal money would no longer be able to discriminate against disabled service users or employees. In essence, this provision would mandate the existence of elevators, ramps, and equal employment and education opportunities across federally-funded organisations nationwide.

Initially, Nixon vetoed the bill, claiming that the costs involved in providing equal access were too high. In the spring of 1973, a group of disabled activists stopped traffic across four blocks of Manhattan and forced the President to sign, but he did little to enforce the provisions. By 1977, and with Jimmy Carter having taken office, disabled activists had lost patience. Led by the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities, they occupied federal buildings across the United States.

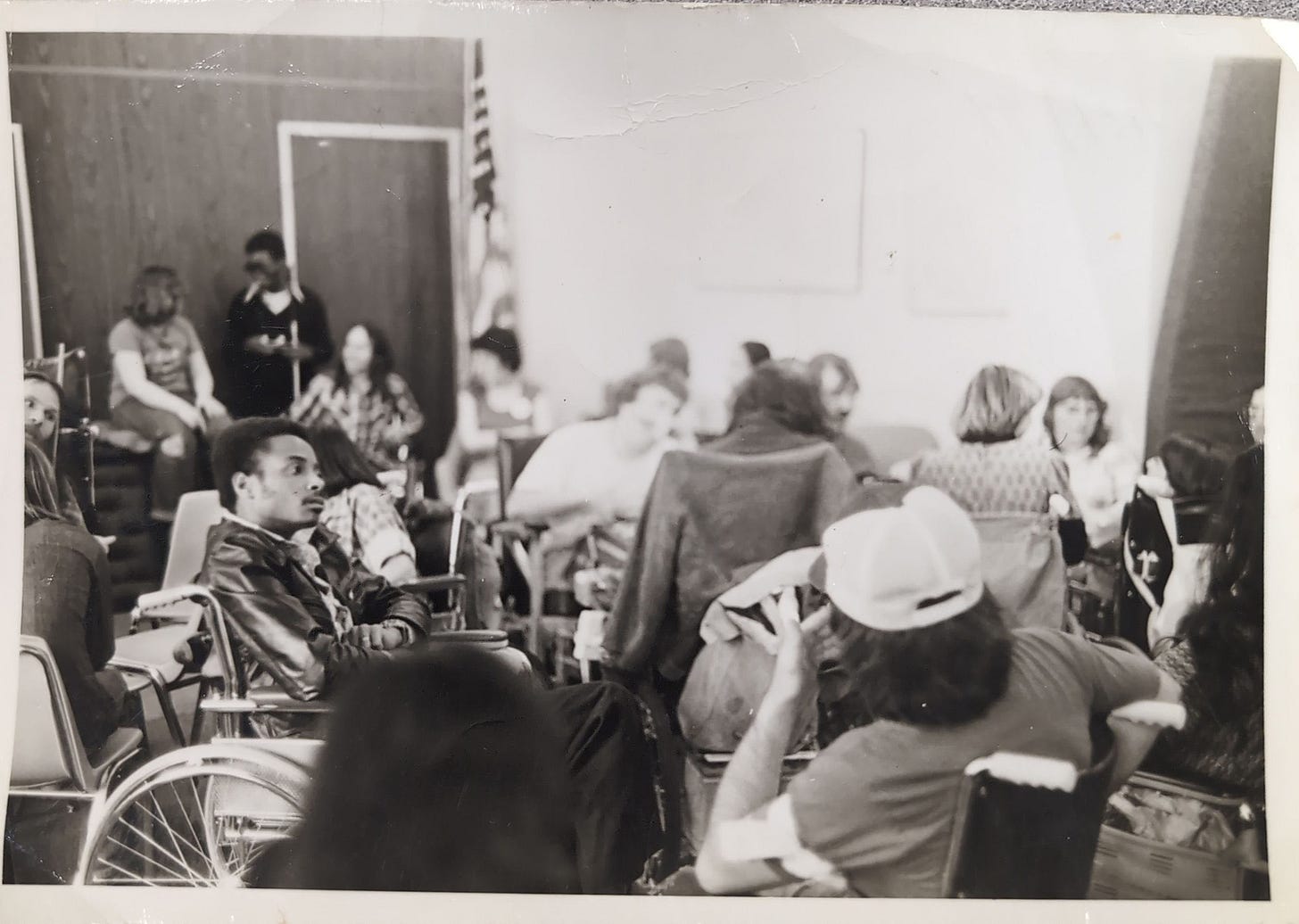

Over the first few days, many sit-ins fizzled out as the buildings’ water and power supplies were cut and disabled protestors were forced to leave. But the one that endured was in San Francisco, where Judy Heumann and Kitty Cone led a group of multiply-disabled protestors and allies on the longest occupation of a federal building in the history of the United States. The 150-strong group held out in the United Nations Plaza Federal Office building for an incredible 26 days. They were only able to last so long because of Brad Lomax and the support of the Black Panthers.

Brad himself, along with his attendant Chuck Jackson, helped to lead the occupation, and also maintained contact with the Panthers from inside the building. With the links the two groups had forged in previous years, the Black Panthers provided the disabled protestors with hot meals every day, reported widely on the protest in their newspaper, and even funded the protest leaders’ travel to Washington D.C. to see the new law signed.

“Without the presence of Brad Lomax and Chuck Jackson, the Black Panthers would not have fed the 504 participants occupying the HEW building,” wrote disability rights organiser Corbett O’Toole. “Without that food, the sit-in would have collapsed.”

Eventually, on April 28, 1977, the regulations were approved, marking the beginning of federal disability protections across the United States.

An enduring legacy

Following the sit-in, Brad never really recovered from ongoing complications related to his condition. He died on August 28, 1984, at the age of only 33. But even though his life was so short, his impact can still be felt today. The 504 regulations may have only applied to federally-funded programmes, but they also laid the groundwork for the Americans with Disabilities Act, which passed thanks to huge activist involvement in 1990 — and involved many of the same disability leaders from the 70s.

Without Brad Lomax and the involvement of the Black Panther Party in 1977, it’s likely the ADA wouldn’t have existed. At the very least, it may have taken far longer for it to be enacted. Disability rights in the US were forever changed by the 504 sit-in, thanks to solidarity between two communities, and one brave man who built a bridge.

Further Reading and Watching

· Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution (2020) - Netflix

· Overlooked No More: Brad Lomax (2020) – The New York Times

· Fading Scars: My Queer Disability History (2019) – Corbett O’Toole

· The Disability Rights Movement: From Charity to Confrontation (2011) – Doris Fleischer and Frieda James

· Lomax’s Matrix: Disability, Solidarity, and the Black Power of 504 (2011) – Susan Schweik, University of California at Berkeley

My debut novel is out in June! Pre-order Awakened and send me a screenshot, and get a 6 month subscription to Substack for free