notes from an unruly body: Discovering Eva Gore-Booth

Poet, playwright, and queer suffragist

“There is a vista before us of a Spiritual progress which far transcends all political matters. It is the abolition of the ‘manly’ and the ‘womanly’. Will you not help to sweep them into the museum of antiques?”

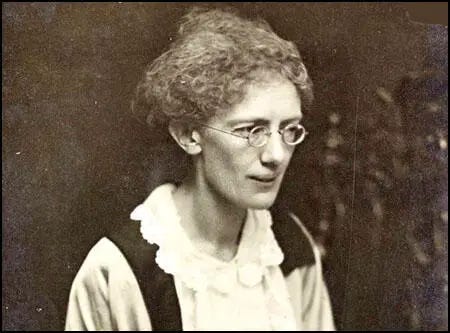

Eva Gore-Booth (1870 – 1926) published this in the magazine Urania shortly before her death. It came at the end of a life that included an aristocratic upbringing, a friendship with W.B. Yeats, a lifelong and most likely lesbian relationship with her “companion”, the leading suffragist and activist Esther Roper, and a move from Ireland to Manchester.

By the age of fifty-six, Eva Gore-Booth marked herself as a poet, an author, a playwright, a suffragist, a campaigner, and a Trade Union member. But it’s likely that, had her health never suffered, many of these achievements might not have become a reality.

Early life

Eva was the third of five children to be born to Sir Henry and Lady Georgina Gore-Booth in County Sligo, Ireland, on the grand Lissadell estate. Like her sister, Constance, (later to become Countess Markievicz), Eva was educated by a number of governesses and lived in some luxury. But during the Irish famine of 1879, she became deeply disturbed by the contrast between her family’s comfort, and the people who would arrive begging at their door for food and clothing.

Later on in her life, Esther would remark that Eva was “haunted by the suffering of the world, and had a curious feeling of responsibility for its inequalities and injustices.” It was this feeling that inspired the remarkable campaign work that would take up most of her years.

First, though — and unusually for the time — Eva would join her father (himself a notable Arctic explorer) on a number of his travels around the world. In 1894, she sailed with him to North America and the West Indies, keeping a diary for much of their trip in which she documented their explorations. Upon their return to Ireland, she first met the poet W.B. Yeats, who was impressed not just by her travel accounts, but also by her other writing.

“I’m always ransacking Ireland for people to set at writing Irish things,” he wrote in a letter that year. “[Eva] does not know that she is the last victim — but is deep in some books of Irish legends I sent her and might take fire.”

But the great turning point of her life was still to come in the following year. On a trip around Europe with her mother and sister, Eva contracted a violent respiratory illness that led to her being forced to recuperate at the villa of the writer George MacDonald. It was there that she first met Esther.

Convalescence and conscience

Reports differ about the exact nature of Eva’s illness, but it seems likely that she contracted consumption (better known now as TB), and at the point of her convalescence in George’s Italian villa, it was feared that she was near death. The illness would instead become chronic and lifelong, leaving her frail for the rest of her life, but her association with Esther proved to be the spark that ignited her work.

Esther was already a leading suffragist and activist when the two women met, and although she believed that she didn’t have much time left in the world, Eva left Italy with her. But they didn’t return to the comfort of her family home in Ireland. Instead, they moved to the industrial city of Manchester, England, where Eva threw herself into work alongside Esther, helping the female factory workers there organise and fight for better working conditions.

In 1900, having passed through the worst of her illness and learnt to live with its effects, Eva became a leading figure of the Manchester and Salford Women’s Trade Union Council — and the council itself would become a huge influence on a number of female Unions that came later.

Over the following years, Eva would help campaign for many political candidates who supported women’s suffrage, and eventually her work brought her into contact with Christabel Pankhurst, a leading light in the suffragettes. In 1908, she was a delegate to the Labour Party conference in Hull, where she proposed a motion in favour of women’s suffrage which was disappointingly defeated.

By the time World War One broke out in 1914, Eva had established herself as a voice for both equal rights and peace. In 1915 she became a member of the Women’s Peace Crusade, and in 1916 the No- Conscription Fellowship.

As her health began to deteriorate again, more and more of her work focused on writing on both of these subjects in various forms.

Literary legacy

Eva was associated, in her time, with the Celtic revival of work at the turn of the 20th century. By the end of her life, she was the author of nine books of poetry, seven plays, and many collections of spiritual essays and studies of the Gospels. She also wrote a number of pamphlets and essays related to women’s suffrage and her strongly-held belief in pacifism.

Her poetry, in particular, was remarkable for its insistence on emphasising the women in Irish folklore. In her work, Triumph of Maeve, she makes the meeting between Maeve and a wise woman erotic, and much of her poetry features love verses written from one woman to another in some form.

Eva eventually lost her life to a particularly aggressive form of intestinal cancer in 1926. Although her sexuality was never explicitly labelled during her lifetime, she made Esther Roper, her lifelong companion with whom she also owned a house, the sole beneficiary of her estate.

Further Reading:

· Eva Gore-Booth – The Poetry Foundation

· Eva Gore-Booth: Collected Poems (2018) – Sonja Tiernan (editor)

· Eva Gore Booth and Esther Roper, A Biography (1988) – Gifford Lewis

· The Political Writings of Eva Gore-Booth (2015) – Sonja Tiernan (editor)